Understanding Differential Power Analysis (DPA)

Cryptographic algorithms are designed to be secure against direct algorithmic attacks, but their implementations often have vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities can be exploited through implementation attacks, which are methods of bypassing cryptographic protections by targeting their physical or digital execution.

In this post, we’ll dive into passive physical attacks, particularly focusing on power-based side-channel attacks, with an emphasis on Differential Power Analysis (DPA). If you’ve ever wondered how power consumption leaks sensitive information, this post is for you.

What are Side-Channel Attacks?

Side-channel attacks exploit physical emissions or behaviors of hardware during cryptographic operations. Instead of attacking the algorithm itself, these attacks gather indirect information such as:

- Electromagnetic (EM) emissions

- Acoustic signals (sound-based)

- Power consumption

Among these, power-based attacks are the most widely used due to their relative ease of implementation and effectiveness.

Why Attack Implementations?

Cryptographic algorithms like AES and RSA are incredibly well-tested and designed to withstand mathematical attacks. However, the implementation of these algorithms in software or hardware often introduces weaknesses. Side-channel attacks exploit these implementation flaws without breaking the underlying cryptographic principles. Kerckhoff rolls around in his grave every time you ignore the algorithm btw.

Power Consumption

To grasp how power-based side-channel attacks work, let’s briefly explore how hardware consumes power.

Switching Activity of Registers

Most digital circuits—such as microcontrollers and FPGAs—consume power when the state of a register changes. This power consumption depends on:

- The number of bits toggling (switching from 0 to 1 or vice versa)

- The underlying hardware design

For instance, in CMOS circuits, dynamic power is proportional to the number of transitions between states, making the power consumption correlate with the processed data.

How do we extract small correlations from noise?

We do a lot of measurements. Thousands. Correlation is then preserved, and random noise cancels out.

Attack Surfaces

Let’s take a look at this code. Assume our input and password are both strings of a length of 8.

for i = 0 to 7

if (password[i] != attempt[i])

return 0

return 1What’s the theoretical security level?

If you think it takes 2^(8*8), which is all possible 8-byte combinations, you’d be incorrect.

Because we’ve taken away the methodology to compare the entire attempt string to the password string, we’ve actually reduced the surface of the search space to 2^8 * 8, which is 2^11.

This is how side-channel attacks work. Instead of attacking the algorithm itself, we attack the implementation of the algorithm, which is not always done correctly.

Power Side-Channel Attacks

Types of attacks

- Profiled Attacks

Pre-characterize the device and build precise models

Examples being

- Template Attacks

- ML-based Attacks

- Non-Profiled Attacks

Using generic power models

Examples being

- Differential Power Analysis

- Correlation Power Analysis

- Mutual Information Analysis

Hamming Who?

Hamming weights and distance are critical to power analysis.

- Hamming Weight is measured as the number of 1’s in a binary value.

- For example, 0x1101 has a hamming weight of 3.

- Hamming Distance is measured as the difference between previous and current hamming weight.

- For example, the hamming distance between 0x1101 and 0x1001 is 1.

Microcontrollers often exhibit power consumption proportional to Hamming Weight, while FPGAs often follow the Hamming Distance model.

DPA

- Apply an input to the target device.

- Measure its power consumption during cryptographic operations.

- Hypothesize intermediate values (e.g., partial results of encryption).

- Group power traces based on key hypotheses.

- Compute statistical metrics (e.g., Difference of Means, correlation tests) to identify the correct key.

We can use different metrics in DPA attacks.

- Difference of Means (DoM): Measures the difference between group averages.

- T-Test: Determines statistical significance of differences.

- Correlation Tests: Identify relationships between power consumption and hypothesized data.

Hands-On Attack

I wanted to get a hands-on introduction to power-based side-channel analysis. An implementation of AES-ECB was created and I took a set of power traces during the execution, with the associated input/output values of AES, and I performed an attack to extract the 128-bit secret key via DPA.

The power traces contained 10,000 AES-ECB executions, with random input and a fixed, secret key.

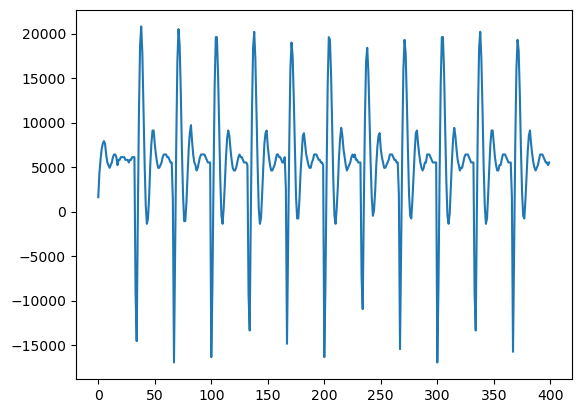

Power Trace Analysis

Let’s take a look at the power trace itself, and the data we have in it.

The peaks in the trace (both peak and trough) are the maximum leak points.

These peaks indicate the specific time for an adversary to retrieve the secret key.

These signify the 11 addRoundKey() functions in AES-128 bit encryption.

Attack

Analysing the first power trace

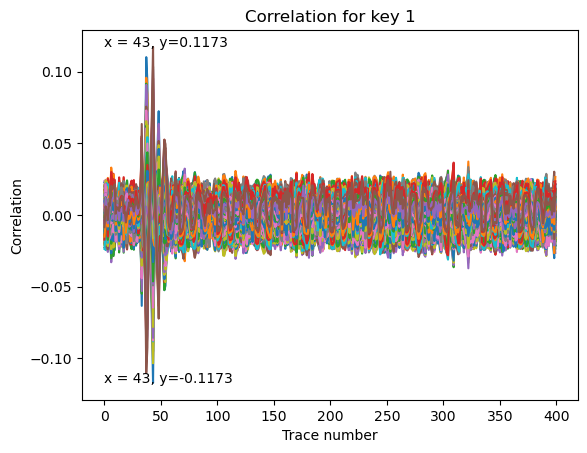

Let’s execute the DPA attack using Pearson’s correlation test. We’ll take a look at the power trace, corresponding to the first encryption operation.

- Think of an easy target operation for the DPA

- Consider the number of bits to be estimated by DPA at a time.

The AES implementation was done on an FPGA, therefore, we will use a hamming distance power model. For each input byte, the FPGA will store the initial input, then we will perform the addRoundKey operation.

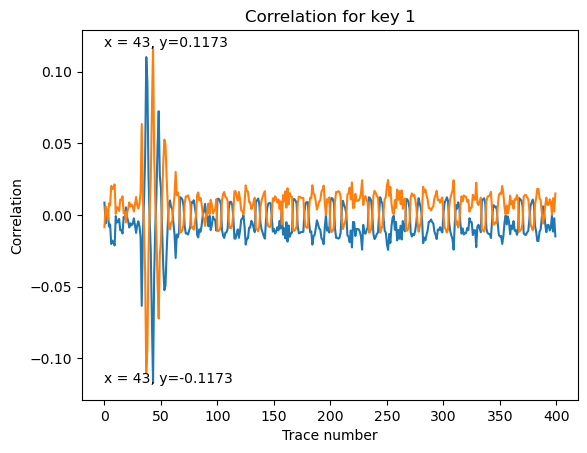

Breaking Apart the Maximum Correlation into 2

Both lines are symmetrical to each other. The negative graph is more likely to be the correct

guess, because it looks more like the power trace.

This is key = 0x00.

Finding the Maximum Leak Point

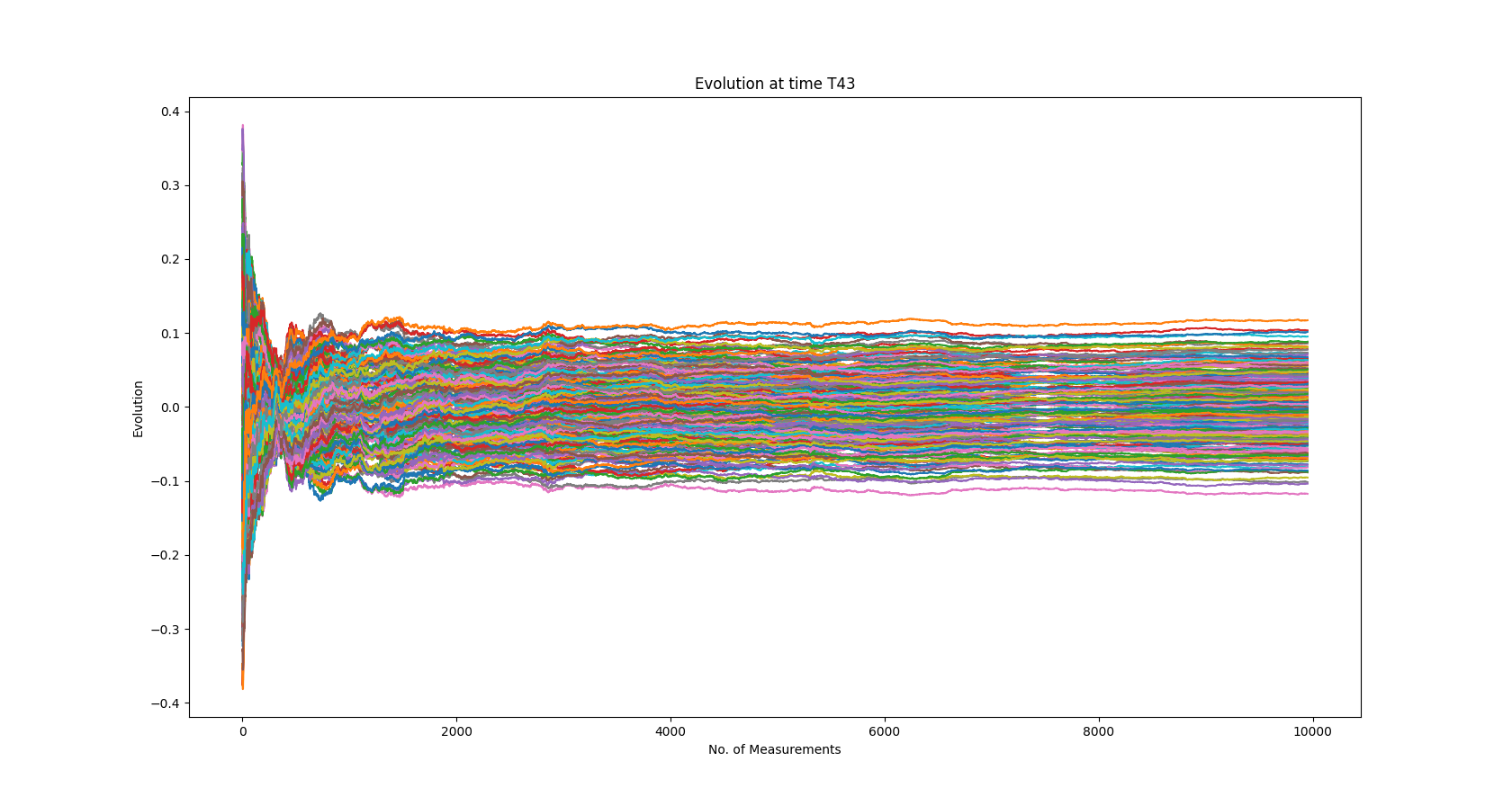

In time domain, the maximum leak point is t = 43. This is a plot of the “evolution” of key hypotheses for all measurements at t=43

We also see that we can figure out the key after t is approximately 1580.

Applying DPA on the entire key

After applying DPA, we see that the key is

0x00 0x01 0x02 0x03 0x04 0x05 0x06 0x07 0x08 0x09 0x0a 0x0b 0x0c 0x0d 0x0e 0x0f

Compared to a traditional brute-force attack of AES (which takes 2^128 attempts theoretically), our reduction ratio is log10(2^128)−log10(10000) ≈ 38.53184 − 4 ≈ 34.53184

Prevention

We can make this harder by doing several things.

- Precharging the bits when we perform the XOR, such as in a microprocessor

- This equalizes power consumption

- Injecting random noise to mask power traces

- Obfuscate data and operations by adding unpredictable methodologies to perform operations

- Other hardware countermeasures exist, we’ll talk about them in later blogposts!